Visual Arts Andrew Bartels, Kimberly Trowbridge, Robert Hardgrave, Sharon Arnold — April 11, 2012 15:59 — 1 Comment

The Way Thought Moves

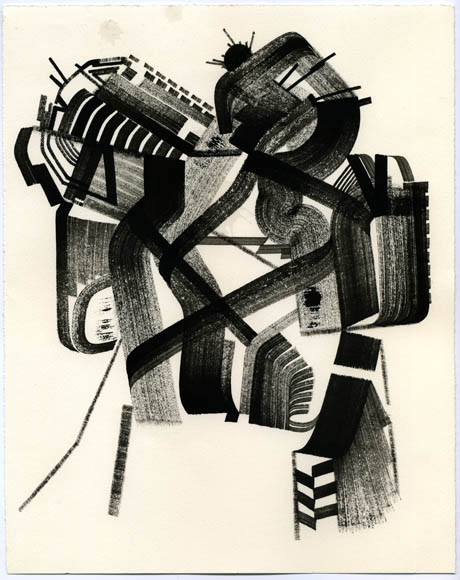

Robert Hardgrave “Reminiscent” (2012) gouache and crayon on paper 6″ x 6″

I recently had a conversation with the poet Caleb Thompson about the difficulty of “following a thought,†of moving logically from a preposition to a conclusion. He had been reading quite a few essays and was perhaps feeling awed by the talent these writers possessed of cutting through the static of daily “thought.†I replied that good essays are not an accurate record of a mind in motion—the literary equivalent of Muybridge’s photographs might be the Surrealists’ practice of automatic writing—the mind works through tangents, association, gaps, false memory, distraction. An essay that is well-structured, revelatory, and dense with meaning attains its form because the writer is able to rearrange thoughts on the page, to discover connections, and cut out fluff—to craft meaning.

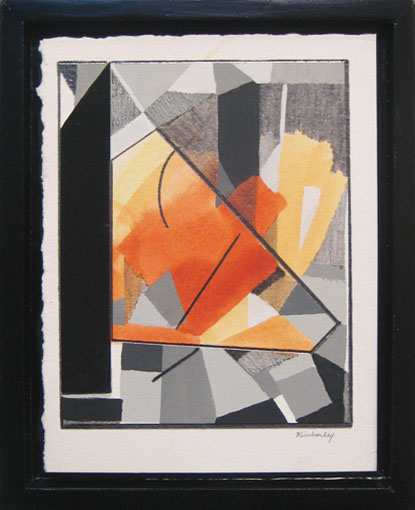

If the essay seeks to clarify by cutting through static, maybe the paintings of both Kimberly Trowbridge and Robert Hardgrave build a static charge. In certain paintings that are densely patterned (whether the angular, “shattered†structure of some of Kim’s large works, or the sinuous tangled lines in Robert’s), a spark between the abstract mark and its array of visual suggestions produces—to continue the electrical metaphor—an alternating current in the brain. This visual energy engages the viewer in the same mental exercises as the painter. In this case, the exercise is not of depicting a scene, but of moving from mark to mark, from thought to thought, in a constant attempt at discovering form and outdoing the self. The “big picture†can never be taken in at once—and why should it? All the fun and pain are in the details. These small images of Robert and Kim are all detail, sections of a larger project of perception, maybe even gateways—electrical conduits—to the larger works.

Kimberly Trowbridge, untitled (2012) gouache, graphite, and collage on paper, mounted in wooden frame  7″ x 5.5″

Traveling through the Dark

A writing professor of mine once said that writing a novel is like driving at night on a deserted highway. You can only see so far ahead, yet within this limited circle of illumination you are able to navigate the rest of the highway and arrive at some nameless town.

Getting it Right

Language is a game of combination, of picking up one word and seeing how it looks next to another, another. Gertrude Stein was a champion of this game. Her poem “A Center in a Table†begins: “It was a way a day, this made some sum.†I feel I know exactly how this sentence was written, or at least how the first rhyme, “way†and “day,†lead to the second rhyme, “some†and “sum,†and the cleverness of that discovery. Can there be such a thing as visual rhyming? Kim has often talked about value in reference to her paintings—that is, different colors that have the same lightness and intensity (just as “some†and “sum†have the same sound-value). Stein claimed to be trying very hard to capture the essence of objects in these poems, but as much as she may have been reacting to a visual world I think she was (inevitably) reacting to what was on the page, her own words. Later on in the poem:

“Next to me next to a folder, next to a folder some waiter, next to a foldersome waiter and re letter and read her. Read her with her for less.â€

The slightest variation of “next to a folder some waiter†yields a “foldersome waiter.†The latter is surprisingly evocative, and illustrates Stein’s “innumerable efforts to make words write without sense,†which she found “impossible.†In general, painting may have a visual parallel—the associative quality of blue and sky or water, green and grass, red and blood—that accounts for the suggestiveness of the most abstract of paintings. The meaning of words and the associations of color, however, are a given. A more interesting parallel can be found between Stein’s signature repetition and Kim’s sort of visual “echoes,†repeated shapes and gestures that vibrate outward from a central figure. Like a stutter, the repetitions give the sense of consecutive attempts to get something right. When one is dealing with a difficult subject, the gesture of a shoulder, for instance, one must fixate and draw it again and again. For instance, the gesture of a shoulder happens again and again. One must fixate on the shoulder to get it right.

Kimberly Trowbridge, untitled (2012) gouache and sumi ink on paper, mounted in wooden frame  7″ x 5.5″

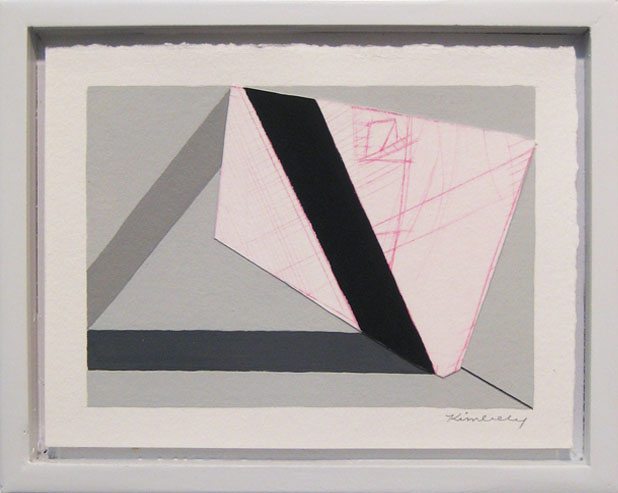

Palimpsest

Palimpsest, from Greek – scraped again, originated during the days of parchment and papyrus. Writing surfaces were so valuable that they were reused, the original text effaced to make way for new writing. Building a city over ruins. Often, the older text was still visible and even legible “underneath†the more recent text, literally creating layers of meaning. This is an idea that Kim and I have talked about as a concept of revision and of presenting a painting or poem as an historical document. Not some static image, but a record of revision. This is a groping way about things. You begin, you create a failure, some lines, then there is something to react to. You make some changes, the work progresses. You think to yourself: “That is not right†or “The world has completely changed.â€

Distinction

“The Medium is the Message.â€Â ~Marshall McLuhan

“A change of style is a change of subject.â€Â ~Wallace Stevens

Kimberly Trowbridge, untitled (2012) gouache and graphite on paper, mounted in wooden frame  7″ x 5.5″

Collage and Thingness

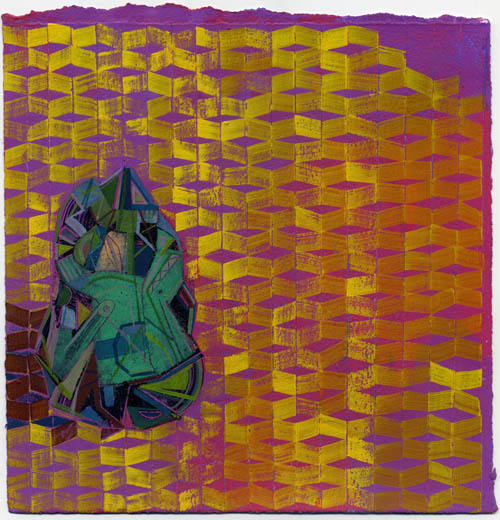

By now, we’re familiar with the conventions of presenting a whole through its various parts: a street scene through a montage of images, trash and artifacts, stitching together a portrait with various faces, a major news event conveyed through multiple interviews. The collage mode has pervaded all the arts, from T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, to hip-hop “sampling.†In painting, one can’t get around the idea of the image as a collage of moments and a sampling of the visual world. Robert has taken this idea a step further in collaging and sampling his own canvasses and drawings. Instead of painting over an image (as in a palimpsest), he cuts it up and rearranges it; the already intricate patterns become even more abstracted and mixed together. At the same time they become more physical. Rather than presenting an image, the “painting†seeks induction into the world of things, to assume its true thingness. It’s appropriate that these canvas and burlap collages take shape as Frankenstein-like figures attempting to leap the divide between image and thing, to become objects of fascination in themselves with their own growth and agency.

Analysis:

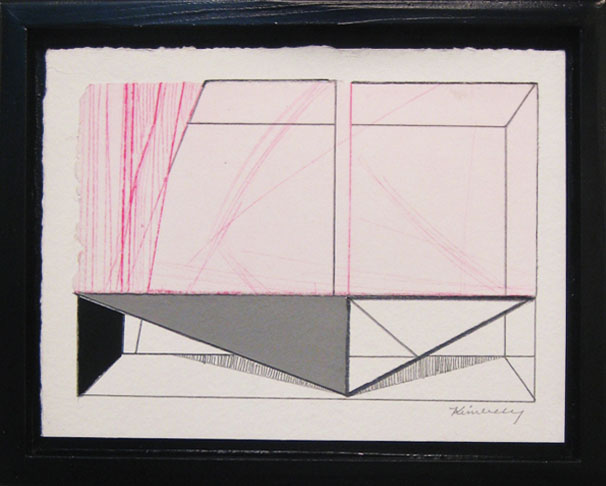

It is usually the role of the critic or theorist (rather than the painter) to separate a subject into parts for individual study. Of course, the term was famously employed during the reign of cubism in the early 20th century. In Kim’s recent “Bolted Dream†series of paintings, and her “Arcadia†series, the figures or their environments are often fractured, broken up into discrete planes reminiscent of that tumultuous period of painting. While not visually the same, Robert’s new figures of sewn burlap are constructed from pieces of his drawings, a clash of pattern, texture, line. The architecture of the whole figure is a conglomerate of distinct passages. This fracturing and collage of the figure is in no way de-constructivist (death of the author, dissolution of objectivity)—it is genuine self-reflection and meditation on the pieces of the self.

Kimberly Trowbridge, untitled (2012) gouache and etching collage on paper, mounted in wooden frame  7″ x 5.5″

Sub-Analysis

Analytical—maybe that’s not quite right. The Analyst attempts to understand a large subject (DEATH, for instance, or the SELF), by breaking it down to its constituent parts. Once those parts are understood, then knowledge or experience of the whole is rendered. Perhaps what’s at work here is a subverted analysis, sub-analysis: beginning without the subject, making a mark on the canvas, reacting to that mark. Feeling a thought, reacting to that thought. It’s necessary to put the grand themes out of the head and begin operationally to build a matrix or pattern of these impulses, thoughts, and decisions. Inevitably, the subject will appear, with “each part of a composition being as important as the whole.†–Stein again.

The Trance of Clarity

The painter Whiting Tennis once explained a drawing exercise in which he would connect the dots in a small grid with straight lines, always attempting to circumvent impulse—if he felt the urge to draw a vertical blue line, for instance, he would draw a horizontal red line. This is a mind game as much as a drawing exercise, one that forges new pathways in the brain as it breaks habitual, visual constructions. Robert described a similar process of resistance in his recent drawings—resisting familiar ways of resolving a shape. What might appear to be automatic drawings are quite the opposite. (semi-automatic drawing?) The purpose of automatic drawing is to access a supposedly suppressed part of the brain—the subconscious. I can’t be sure, but I would venture to say that Whiting’s exercise and Robert’s process of mental editing are exercises in awareness, of engaging consciousness. The occasional look and feel of ritual pattern or tribal markings in Robert’s work (some of Kim’s recent paintings are similarly redolent of Navajo weaving patterns) is evidence not of transcendence or escape, but a trance of clarity. That’s the internal paradox: visually complex works that generate myriad associations and meanings—that are charged with the energy of their making—and created, ideally, in moments of intense clarity.

Kimberly Trowbridge, untitled (2012) gouache and etching collage on paper, mounted in wooden frame 7″ x 5.5″

One Comment

Leave a Reply

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney

Wonderful connections, illustrating the way things in all facets work, fail, and succeed because of the looseness and strength of language in the visual and the poetic. I’ve now enjoyed reading this three times, and with each reading, I get something new!