Fiction Devin Walsh — October 2, 2012 12:42 — 1 Comment

The Fabulists – Devin Walsh

The ridiculous version: driving away from the Laundromat one day, she was mesmerized by the sway of his Toyota’s truck nuts, followed him home and, when confronted, confessed to as much.

“My what?†he said. It was a weird trend of the time that his co-workers spent rather a lot of energy vandalizing his Tacoma. Had imprisoned a Shrek figurine in its grill (many thought the two shared an uncanny resemblance). Had fixed it with a bungee cord around the tow bolt to a tree. Real funny. But if it weren’t for that gently-rocking-to-and-fro oversized rubber scrotal sack dangled beneath his fender, would he ever have met his wife? And what in God’s name had come over her, anyway, that she’d literally follow a strange man’s balls home—and not have the sense to deny it?

Well, obviously more had been going on in her bean that day than met the eye, though over the years her version of the story proved impressively durable. I was behind you on the road, saw the truck nuts, became mesmerized…going on to explain that his calm inquiry in the driveway of his rented house—big round face, gap in the front teeth, alertly amused, suspicioning down at her through the open driver’s side window (“Are you following me?â€)—was the first thing she could remember actually happening since pulling out of the Laundromat. (“I don’t think so. Does it seem like I am?â€

“Well, you just parked behind me. In my driveway. And it’s not so big…so you’re sort of sticking out into the road, and everything…â€

“Oh, that honking?â€

“Yep. That’s at you. Sure is.â€

And then, yes, I offered—

Think I insisted—

You come up, glass of water—

Clear my head—

Fold your laundry, if you want—

After I’d re-parked my car, of course—

And. Yeah. That was that.

We fell in love.

###

The “meet cute†version was they’re both on the lee side of a weekend away from wedlock with wistfully, ironically recalled others, enrolled in bachelor’s and bachelorette’s parties fatefully paired the same night in a roving local event called the “Brews Cruise,†in which barley enthusiasts undertook to get soused visiting three or four local breweries, chaperoned by long-suffering thirtyish employees who plied them with pretzels and Ritz crackers between stops.

At one—they forget which, hard though that is to believe—a blues singer had brought a big crowd of howling gray-haired men and lascivious heavy-breasted women with expensive dye jobs and dancing shoes. Evidence of dipsomania littered the dark barn of the brewery: half-drunk pint glasses laced with foam marooned in strange places; unattended dogs exercising all manner of promiscuities in ways not entirely dissimilar to the human strangers among whose shoes and knees they made love, becoming acquaintances, becoming friendly, and finally pledging to each other their eternal fidelity, affection and sacred honor, from this point forward, God as my witness. And if He can’t be found, why not this guy…? What’s your name, buddy…?

In the general noise, pitching and frothing like ale in unsteady fingers, you’d be forgiven (the prospective Maid of Honor and Best Man were—in time) for missing entirely the life-changing introduction that happened outside the establishment’s single, overworked bathroom.

“Simon,†said the Groom-to-Be to the Bride-to-Be, shaking her hand.

Smiling up at him, “Actually it’s Claire.â€

Things went from there. Quickly.

###

Or, what was it called, our band? Ah yes: The Technique. Simple as an ad answered in a weekly zine: Experimental Musicians Needed for Eclectic Project sort of thing…give us your cellists, your Kazooers, your collectors of percussional curios…

She had the waify appeal contrasted with the haunting alto; he the vault of quiet, noiseless and hardly moving in the nexus of all that sound, fingers you never seemed to see in motion magicking up melodies from instruments you never seemed able to readily identify.

Groupies swayed in trances affected and un-, strangers called by the music, interlocking hands, touched by odd breezes of memory, lives they couldn’t be certain belonged to them all of a sudden seeming fragile, beautifully fragile…

Claire then had ditched her standby look (short-brimmed Army Surplus hat, frayed khakis, rainbow belts, old cotton tops with buttons lost somewhere in the world, combat boots, tea-colored hair mousy behind her ears, eyes green as Leprechauns) and adopted a persona more behooving the tragic figure of the many-times-burned lounge singer, complete with outstanding fake eyelashes, bruising mascara, a wig the color of blood and flowing black dresses that suggested in her portfolio of aggrieved poses the shapes of loss and of sex. Not as often as you’d think did a guy offer to pick up her tab, and maybe more often than you’d think a woman would, perhaps recognizing in Claire some wounded double in need of kindness, as if kindness was enough to mend those years’ worth of ineradicable pains…

Simon, outside, between sets, shrouded in the reticulating smoke of his long cigarette, gravely accepting the proffered compliments of musical young men brave or drunk enough not to fear him…

In this version—starchy, ostentatious, and almost entirely lacking in substance—the two fell together conjugally as if by mathematical imperative. Joy would’ve interfered with songwriting. The sex was mournful and sometimes mean. But what can you say about musicians that hasn’t already been said about lunatics? Except: occasionally they make reasonable decisions for tax purposes. Voilah: knot tied.

###

Inevitably they find themselves in an anonymous apartment or condo, all the walls blank and white, all the shades—if there are windows—drawn. Fear, in the space of a breath, is total, animal, hysterical. And when the craze has eaten enough of itself to slow, sluggish with its gluttony, Thanksgiving-dinner’d, heavy-thighed, growing sleepy, a tiny glimmering ray of light punctures the miasma… Just an idea, the weight of a thought. How was it, again, we met?

Well, let me tell you…

###

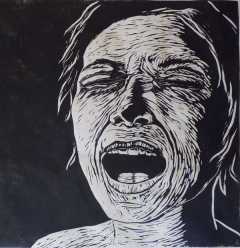

A favorite for an overcast day was the mourning version, the one about the interruption of grief. This opened with the image of a young woman—it’s Claire—wracked and inconsolable, enlisted in a self-internment within the auspices of her small, once-tidy apartment, going gradually to seed, its walls painted pale shades of light, butter, cornflower blue…the fact of her internment better described as necessary than rehabilitative.

It’s worst for people with small needs, her sister said over the phone. They never see it coming.

Though she’d wonder, not idly, what did it matter if you saw it coming or not? What did it matter when the thing was juggernaut?

She logged all of depression’s usual low points: complete loss of appetite, disinterest in food in general, even flavors left her, as though her tongue’d been scorched; fear of the phone finally led her to throwing it out, sister be damned (it was harder, anyway, knowing she lived Out There, in the perpetual and unremarked sunshine of them who didn’t know shit, forcing herself out of sisterly obligation into these morbid vacations to the other shore); naturally she stopped checking the mail…how easy it was, actually, to withdraw from the world.

Grief was the truest human action, the best and sanest response to living. Utter nonsense, the rest of it. Endeavor. Politics. Art. How ridiculous, that tiny people attempted to hold in the flimsy bowls of their minds a concept like God! She used to try, sitting on a toilet, say, or watching a bird on a fall day, enjoying a rare smoke, her little mind striving to compass the deity—fool!

Now it was bed, long indulgent baths, picking at whatever wasn’t rotten in the fridge.

One night: milk.

She hadn’t been sleeping so much as observing—not without amusement—her thoughts unravel into incoherence, marveling at the habit of her brains to fracture into places and pieces without number. Feverish, sweaty, tangled like challah bread with her sheets, Claire got up and, in the sickly refrigerator light, downed a half-gallon of skim milk. It streamed down her chin, pooled somehow in her left ear, plunged like white vines down her slender neck and between her breasts, falling so quickly it was as if the trails of milk had always been there, only illuminated instantly by some hitherto unknown light, fugitive from extremes of the spectrum.

Returning to bed, her dreams were a blessed white, the bowl of her mind peaceful with milk.

In the morning, for the first time in weeks, she left the apartment and filled a grocery cart with skim. She didn’t bother lying to the cashier. Best not to talk. Grief loathed an explanation, adored a vacuum. People should know, anyway, instinctively. They should recognize it. Truth standing before them, walking among them, wreathed in black no matter the color of its clothes.

After a while, skim didn’t cut it. She advanced to 1%, then 2, drinking it constantly, unremembered cups in every room, turning blue, coagulant, radiant with sour notes. She’d throw up and drink more. Whole milk. Milk was what was real. She thought often of her mother, who’d gone with formula to save her breasts. She’d made sharp-edged jokes about how greedy Claire was, how she’d chewed and bit. She wanted mother’s milk.

Got online, when even whole milk got too thin, and learned of a dairy farm in Canada that sold the raw, unpasteurized stuff direct from the teet to its subscribers. (Subscribers, they called them, like a baby subscribes to its mother.) Learned all about pasteurization—how it had the effect of rendering whole generations prone to disease, their immune systems unbolstered by the early years of war against bacteria; how a free-range, grass-fed, organic dairy ranch in California was shut down when regulators diagnosed the cow’s shit as unsuitable. And why? Because a century of feeding cows cows and pumping drugs into them had altered the nature of the species’ stool until the error usurped reality.

She went to Canada.

Heading up the ranch was a cheerful septuagenarian who claimed to have cured his cancer with a diet of pumpkin seeds and raw milk. God had told him the recipe. He had pamphlets. The sandniggers, he said, took raw camel milk for cancer, but that was horseshit. He wore overalls, his hands were old red meat, and he spoke ceaselessly for about an hour, showing her around on a sunny day that smelled like cut grass. Barns. Old trucks. Sloping grassland decorated with bovine lawn jockeys under a cloudless sky of fierce blue. Cows always resembled a painting of cows. Claire withstood the verbal onslaught for the milk. At length, after she’d accepted a pamphlet, he released her to the care of a lean, laconic cowboy—the old-timer’s protégé in vocation if not personality—who introduced himself, reluctantly, as Simon.

Alone in a barn, alone with smells and lowings, he offered her a refrigerated mason jar. “From Barbara,†he said.

She laughed, after a moment, and it felt like a mountain had dissolved and vanished inside. “You have a cow named Barbara?â€

Why it was so funny to her she couldn’t say, but it was cruel, laughing at what was so clearly an animal he loved dearly, so she shut up and raised the jar to her lips. The light in the jar had been tempting her, anyway—a yellowish purity. A color it seemed impossible to bottle, let alone drink, as if the merger would necessarily lead to a generalized blanching. Like an animated thing—an evil Queen who’d selected the wrong potion—she’d swallow and at once a cascade of albinism would transform her from split ends to toe nails. Instead she felt a shift, a budging, incremental and disconnected from anything she could have expected, a little like falling in love.

Simon saw it, the shine in her eyes when they finally re-opened, their greens greener and more vital—the lawn after rain—the pink of her tongue lapping up the last pearls from her lips, her breathing and color up, hand fluttering to her heart.

“Miracle,†she said, eventually, wanting him intensely.

Kindred spirits, and all, Simon, with a secretive smile, said, “Try it fresher?â€

And before she could even decide how to feign confusion, he’d crouched down to a lowing piebald Hereford, handy with a pail, gloveless and—God—

Yes! Oh yes, yes, yes…

###

Maybe it was that the milk version seemed the most personal, the most laden with honest human baggage, that tended to cause the crack in the fabulist’s carefully cultivated dream. Sometimes occurring with the subtlety of a firefighter’s axe splitting a door, others with the minute poetry of a seed caught in the wind, a morsel of pollen alighting on a ready bud, or taken from it, either way it was destiny that every so often a germination took the dream from him, and he’d ascend from the warm mud of his pleasant fictive universe into what it dawned on him with relentless speed was a reality no invention could cloak.

White walls. The humming and beeping of machinery. The insipid drone, barking and laughter of a television that wasn’t ever turned off. Odors of sterility it was quite obviously a constant battle to maintain.

Threads cling to his mind like spider web, fading, merging in absurdity, encircling his heart, going away.

There—a hand on his, or his hand in another. A presence. The woman he loved, had loved for so long. Claire. Turned old. Limpid eyes on him, affectionately bewildered. “You say the strangest things, my dear.â€

He could only get about a word out per breath. “Dying,†he said. “It’s.†She waited. “So.†Someone was going to commercial. “Interesting.â€

On his forehead, the warm paper of her soft old hand, her eyes damp. On his cheek. Another ad for milk, of all things.

“You know.†He coughed. “I can’t. Recall. How. We met.â€

His Claire. Her beautiful smile. That way she had of sighing before starting a story. “Well, there was a big, wonderful dance…â€

One Comment

Leave a Reply

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney

love what your nimble mind and flashing fingers hath wrought … the poignant ending moved me. A nice contrast to the absurdity at the beginning.