Essays Shaun Scott — October 30, 2012 12:27 — 0 Comments

November In America – Shaun Scott

It’s November in America again, and I can’t think of two films so significant, loaded and well-done as “Rocky†and “Taxi Driver†to use as a centerpiece in these next few pages for a few reflections about a country in its holiday and election seasons. But before we get into all that, a digression:

There’s a remarkable moment midway through Godard’s “Breathless†(1960) where the male protagonist Jean, on his way to or from one scam or another, pauses in front of a Parisian movie theater to conduct a séance for Humphrey Bogart, whose mannerisms and posture Jean apes throughout the film, and whose indelible mug appears on a poster. The normally irreverent Jean musters more capacity for respect and self-reflection than we see from him at probably any other moment in the movie. In the sequence—a simple shot/reverse-shot movement that ends in an antiquated iris fade—Jean’s beady eyes narrow further as if staring directly into the life-giving sun, his smirk turns suddenly solemn, the smoke of his ever-present cigarette creating an atmospheric haze which dances in front of a shot of Bogart’s image held long enough to make a point.

For all the historical and critical framing of Godard’s film heralding a French “New Wave†of cinema, the bold new class of filmmakers to which he belonged owed significant and avowed stylistic debts to the cheaply-produced B-movies, noir flicks, westerns, and gangster films produced by the American studio system in the 40s and 50s—films which Godard loved in his youth, and referenced in his earlier occupation as a film critic. Hoary stereotypes of those mediums show-up in all of his early work: the icy female protagonist, bungling male criminals (sometimes posed in cowboy hats), and a delight in portraying the seedy underworld of cities. Whether the French New Wave demonstrated new ways of presenting gender, violence, or politics on-screen could be debated until next November to no conclusion, but one inarguable talent paid to cinema by Godard and his ilk in the mid-20th century goes something along these lines: with the added perspective of the critic-turned-director, cinema suddenly became a referential medium of student-directors, turning what was previously an assembly-line enterprise into a demystified personal practice.

The contribution was a boon for critics as it was for filmmakers: directors now brandished the gambit of self-consciously inserting themselves into a tradition of stylizing celluloid that first began in the early 1900s, making their influences, ambitions, and incidentally their peers more a part of the consumption of their work. Too, critics were invited to treat films as artifacts: if acknowledgements of previous filmmakers exist in the work itself, broader discussions about other relevant media and historical events are also fair game. The notion of film as text and context became richer and more relevant than ever.

This setting is absolutely necessary for talking about film in the US after 1970, when the increasing academization of “Film Studies†and the continued transformation of the American studio system began to take hold. In one respect, no film more reflects the frenetic, hyper-referential, film-student approach than Scorcese’s “Taxi Driverâ€, in which perhaps every other scene at least contains overt and admitted reference to other films in the form of borrowed lines, shots, cuts, and art design. In another respect, no film is as schmaltzy, blatant in its avant-garde reconstruction of the dying Hollywood feel-good format than “Rockyâ€, a feature which spawned a billion-dollar franchise of sequels.

Though it was possible to go to a big box-office theater in any major city in November of 1976 and see both films, “Rocky†and “Taxi Driver†are about as different from one another as Philadelphia and New York: one the story of a floundering loan-collector who rededicates himself to a pugilistic pipe-dream and very nearly succeeds after the mother of all sports movie montages, the other a menacing character study of a Vietnam vet who returns to a decadent metropolis and decides on a personal mission to clean-up his gritty surroundings. The films’ introspective foci on troubled male protagonists at a time of profound societal change make Travis Bickle and Rocky Balboa contemporaries, and the 1976 release year and narrative contents of both works make them natural candidates as vehicles to reflect on the national psyche of America since The Bicentennial.

When South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham said in August 2012 that the American Republican Party was in danger of going out of business for want of producing enough “angry white guysâ€, he was calling for regeneration of the conservative mandate to resist certain upheavals in American life that began taking place 4 decades ago. The simultaneous occurrence of the morass in Vietnam, stagflation, and The Energy Crisis shook the foundation of American life in the 70s in ways from which it still hasn’t fully recovered. Parallel to those shakes were the equally impactful plate shifts of increased civil rights for America’s ethnic minorities, Women’s Lib, and changing attitudes towards sex and sexuality.

If you’re a liberal, a tragedy of The American Left’s predominance in the 60s and 70s was that it ran concurrent with unprecedented structural and socio-economic decay, so that it could become easy to confuse the progress being made on some fronts for the backslide happening on others. In particular, from the POV of the white male around whom the entire American social project had yet been constructed, it would probably seem that legislators, entertainers, and institutions were waging a full frontal attack on life as it was known since 1776. Convincing an underemployed Rocky Balboa that “equal pay for equal work†or a sexually-repressed Travis Bickle that “new gender roles†weren’t ideas specifically designed to disprivilege them personally would be a hard sell.

What we know from interviews and DVD commentary of the personal matrix from which “Taxi Driver†sprang betrays the dark and defensive male mind state of at least one of the movie’s chief creatives: a homeless Paul Schrader wrote the film’s screenplay while house-sitting for the woman he attempted leaving his wife for in the late 60s. Dependent on porn and amphetamines, Schrader spent his days in his car driving around a depressed Manhattan cityscape, daydreaming of ways that others were responsible for his personal version of the funk all men seem to find themselves in at some point in their 20s.

A peek at the original “Taxi Driver†screenplay drafts reveal several hints that director Martin Scorsese wisely, but not completely, downplayed: Travis’ initial meeting with his love interest—a secretary at a Democratic Party presidential candidate’s campaign office—originally contained a rant by Travis about knocking “old coots†and colored people off of welfare. In the film’s penultimate scene, Schrader’s original intention was to have each and every one of the criminals Bickle lays waste to be black. What made it into the film speaks just as eloquent to this point: a gratuitous beating administered to a lifeless black thief Travis shoots, a tense stare down between Travis and black pimps in a diner, and an equally ominous sequence where Travis ponders the social and physical supremacy of American blacks on the television show “American Bandstandâ€. Though Scorsese once described “Taxi Driver†as a film he, Schrader, and actor Robert DeNiro “needed to makeâ€, he thought it wrong and insensitive to have all of the main character’s rage be directed at blacks in particular.

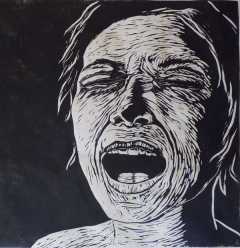

Nonetheless, violence in “Taxi Driver†is a purging force, a blood baptismal for a social fabric filthified by transvestites, “jungle bunniesâ€, and liberalism. Shot beautifully on 35mm stock, the film is a projection of screenwriter Paul Schrader’s, one white male writer’s rendition of the seedy life he allowed himself to become flesh-in-kind with. As the “angry white guy†psyche since the 70s—manifest elsewhere by fictional characters like Archie Bunker, as well as countless real ones in the realm of politics—has been unable to distinguish progress from decay, so too does Travis Bickle remain in confusion as to the root cause of his demons. He oscillates from indignant protestation to eager participation in and of the habits which further his own demise: porn, alcohol, amphetamines, and above all alienation.

Violence, social anxieties, and a certain old-fashioned streak are no less a part of Rocky’s character than they are of Travis Bickle’s, but writer/actor Sylvester Stallone and director John Avildsen approached the presentation of male angst with a fascinatingly different tact. Where Bickle calls attention to his own politics in seething journal entries to himself, Rocky refuses to engage the racial politics of others who cheer his rise from neighborhood nobody to heavyweight contender. In scene after scene loaded like so many decks, the race card is repeatedly played to Rocky’s stultified demeanor. We’re encouraged to view him as a modern-day Cincinnatus of industrial America, Rocky from around the block who fought his heart out for the crown and almost won because the black champion underestimated the power of the proclaimed “Great White Hopeâ€.

Apollo Creed the black champion sets up the bout between Balboa and himself for New Year’s Day 1976, opining that a fight with a white scrapper who pulls himself up by his bootstraps is not only “very Americanâ€, but also “very smartâ€. The night before the heavyweight fight, Rocky visits the ring because he can’t sleep. The publicity posters of the two fighters tell the story of the whole film: Rocky’s effigy stands on the balls of his feet, athletic, primed for attack, ready to rumble. Apollo Creed stands straight-up, non-threatening, smiling wider than the Cream of Wheat faceperson, a perfect portrait of a slick black businessman whose chosen profession is the most palpably violent of all American sports, even as his marketability depends on his success at appearing acceptable and pleasing to white masses. The link to minstrelsy is made explicit after the fight’s opening round, as Creed’s corner men instruct him to “stop shucking and jiving†and take the fight seriously.

For Travis Bickle, physicality was a put-on: he’d pretend in one scene to stop taking “poisons into [his] bodyâ€, and would exercise intermittently to keep self-destruction at bay. Soon the fortitude wanes, and he’s as scrawny and emaciated as ever: peach brandy poured over Wonder Bread is his idea of nutrition; he washes pills down with Budweiser in an exaggerated gargling motion. For Rocky, physical fitness was a way of life, the path to self re-creation. Where everyone else in his neighborhood gears up for Thanksgiving and Christmas, Rocky abstains from sex and regulates his eating habits. His will to resist the over-consumption of the day is made literal and figurative in the iconic scene where he trains for battle by slugging frozen dead cows in a meat-packing fridge.

The point has been made elsewhere by Malcolm Gladwell that boxing’s decline in popularity and significance in America over the last 40 years can be traced in part to the dislocation of the industrial working-class sector of the American economy which fostered the kinds of values, neighborhoods, and lifestyles associated with the greatest practitioners and biggest fans of the sport. Seen in this light, Rocky is a more romantic character than Travis Bickle. For Rocky, there was honor in “going the distance†of a fight with the heavyweight champ; win, lose, or draw, a moral victory existed in fighting with fists, and therefore living to fight another day. For Travis Bickle, disputes are settled with guns, a foray where the consequences of battle are frequently as final and conclusive as the end of the American era marked by The Vietnam War. By film’s end, Rocky somehow wins by losing, while Travis is a mistaken hero. Losers both, moral victory is a spoil the Vietnam veteran can’t claim: Paul Schrader notes that Travis on the streets of NY again is nothing short of a “ticking time bombâ€.

In the end, “Rocky†and “Taxi Driver†seem to me referendums on male conduct, split screens of two pictures depicting distinct modes of masculinity, presentations of the best, worst, and all-in-between of the oft-oppositional American coasts of independence and interdependence. Rocky is no less violent than Travis, but has managed to hone his aggression into a socially-accepted medium. He spends time with the woman in his life at home, a social habit unthinkable for Travis Bickle, a stalker whose third place between work and home is the neighborhood porn theater. Rocky passes on advice to youngsters, and responds to coaxing from older boxing instructors. Travis Bickle is unable to hear an in some ways poetic perspective on life from a well-intentioned but ultimately inarticulate older cab driver. In a subsequent scene—featuring a truly brutish director cameo—he internalizes the homicidal venom of a cuckolded passenger and soon begins stockpiling guns. By the time Bickle positions himself to hand down advice to someone else, his 12-year-old prostitute of a screen partner senses his hypocrisy. The veil of morality stripped, he writes his argument in blood. Both films feature riffs on the famous “Are you talkin’ to me?†bravado, with Travis Bickle’s iteration far more popular because of his murderous intention and intonation. When Rocky utters the line before his prize fight, he’s surrounded by people who wish him well; when Travis speaks it, he speaks into a mirror while christening a pistol, alone in life with the reflection of his own rage.

As examples of The American New Wave, both “Rocky†and “Taxi Driver†took certain cues from their French counterparts around the time of the American Bicentennial: jarring jump cuts and persistent homage show-up in “Taxi Driverâ€, hand-held camerawork and an overall urban realism mark “Rockyâ€. Students of American history might recall that the country’s war for independence was also a Franco-American enterprise. Deep in debt and at war with its largest trading partner in the 1770s, the US cut a deal with France to exchange money from tobacco revenue gleaned by slaves for military aid in fighting the British. The Bicentennial during which “Rocky†and “Taxi Driver†screened was a celebration of the outgrowth of this collaboration. Nations do a strange and circular dance with one another—now at peace, now at war—and the films we make reflect that turmoil just as clearly.

Filmmakers have the opportunity to present more and less sophisticated ways of how to behave towards those closest to us. In the days when digital gloss has all but completely overtaken film, movie magic in the 21st century has less to do with the mechanics of strips and sprockets than with the wonderful light of self-reflection the medium can inspire.

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney