Essays Daniel Davis-Williams — June 6, 2013 12:29 — 1 Comment

Notes From The Croatian Underground – Daniel Davis-Williams

I once believed the Old World still thrived on the other side of the Atlantic. I pictured it sprawling across rolling hills and green pastures edged with virgin woods. I believed its cobbled streets still shined from the abrasions of horse shoes and wagon wheel. That Old World, grand and immutable, was inhabited by good, simple people. Even then I wouldn’t deny that this Old World was now suffused with modern tech and talk, but I doubted these modern intrusions had dimmed the celestial glow of castles and statues and institutions that had survived the hardships of time.

I separated the Old World from the United States by balancing the two on a scale and weighing each society’s accumulated triumphs against the other. The imaginary Old World would trump modern America with every contest. After comparing the Old World’s romantic unfamiliar with the banality of home for many months, I figured enough was enough and it was time to see it for myself.

July, 2010: I arrive in Zagreb with my traveling partner Kayleigh. The train station’s interior, barren and austere and painted in shades of gray and brown, initially belies our high expectations for the Croatian capital. We had hoped for an instant taste of Old World glamour, but the train station’s drab main lobby seems better suited to Stalinist Russia than the remnants of Roman Pannonia.

The disappointment is momentary. As we exit the train station a city bus parked in front of the entrance (temporarily blocking our introductory vista of Zagreb) pulls away to reveal a green, shaded park spanning three or four blocks. A walkway dotted with benches and nineteenth century streetlights runs along the perimeter of the park, stretched from the train station to Old Town. Trees with faded white bark, some nearly three feet in diameter, shade the sidewalk on either side of the park. We walk along the path, admiring sputtering fountains ringed with yellow, red and orange flowers. We see statues of exalted Generals rearing on iron steads.

By the time we arrive at Old Town I stop and tell Kayleigh that it’s all exactly what we had hoped for. She agrees. We are surrounded by buildings, some of them predating the Italian Renaissance, and cobbled streets bisected by tram lines. Old women with bulbous, gnarled noses shove Croatian trinkets emblazoned with the national red and white checkered design in our faces. They yell “fifty kuna!†and lack indignation when we hurry past.

Soon it begins drizzling. Thin sheets of rain coat the scenery, dulling, sometimes hiding, modern inconsistencies that would otherwise betray the fact that we are indeed not in the southern Slav lands of the medieval ages, not in the famed south of Austro-Hungarian dynasties. We walk slowly, examining every corner of St. Mark’s square and occasionally stopping to take pictures, sometimes guessing at the age of this or that stately building. Towering columns of modern architecture – the window-paneled buildings apportioned throughout Zagreb – would ordinarily loom over the horizon on clear days, but on this day, this gray-skied day awash in veiling moisture, the sky’s edge appears empty. There are few cars. We don’t see iPhones or Bluetooths. No businessmen in suits. Nothing that suggests a world in rush. Instead of the usual sounds of sirens familiar to all Los Angelinos we hear the distant toll of cathedral bells.

Satisfied with ourselves for choosing the correct country to confirm our bias, we turn in at a bar. We order steins of dark amber beer and hefty plates heaped with chicken, sausages, beans, potatoes. The bar’s front door is propped open. As we eat we look onto the street veiled in translucent lines of falling rain. The people outside are surely dressed in modern clothing, possibly with cell phones pressed to the left ear and laptops pinched under the right arm, but the curtain of rain hides all evidence capable of contradicting Old World. For all we know, the twentieth century has been aborted.

By the time we finish eating the rain has ceased. The streets are slick, but the Old World atmosphere, now lightly washed over and misted, fits even tighter into our biased notions of Old World aura. We trot along, walking even slower than before, afraid that a quick pace could carry us back into the industrial outskirts of town, back into the twentieth century. Neither of us speaks. We amble along.

But the combo of dark beer and two pounds of pub food (a conservative estimate) begins stewing in my gut, taxing my trot. My focus shifts from the allure of Old World to the uproar of digestion pushed to limits. I hate to murder the mood, but there is no other choice.

I look at Kayleigh, say “I need to find a bathroom as soon as possible.â€

She can’t hear the swamp bubbles roiling behind my abdomen, but she hears the drive in my voice. She nods and asks no questions.

No longer do we pass through Zagreb’s Old Town like pensioners at the Louvre. No longer do we have time to pretend sophistication and remark about architectural magnificence and skilled city planning and the aesthetics of urban greenery. Our only concern is finding toilet. Every passing second without toilet is a tally against Zagreb’s integrity.

But soon Zagreb reveals relief. Wedged between a thirteenth century church and sloping city park is a subterranean staircase. The foot traffic that usually marks a subway station is conspicuously absent. A blue sign posted beside the staircase indicates that only men should descend. Kayleigh wishes me luck. I step down the concrete stairs.

The bathroom is empty when I arrive. Not particularly dirty. No smells so offensive to drive me immediately above ground. I pick a random stall, take a seat. Minutes pass without another sound.

Soon I hear shoes tapping down the stairs. A shadow creeps nearby my stall, establishes itself near the stall door. I remind myself a row of urinals extends perpendicularly from near my chosen stall; he seems to have chosen the one closest to the only occupied stall. This seems odd, but I remind myself that we are all in this together.

But his shadow lingers too far back; he must be standing two or three feet from the urinal. I try to rationalize. Maybe it’s a Croatian custom to piss into urinals like it’s a carnival game. Maybe a foul puddle is blocking his access. Perhaps a gift of nature prevents him standing too close. I give up rationalizing.

Thirty seconds pass. Finally I hear what sounds like a spray-paint can shaking. Ah ha! A graffiti artist! I had seen brick walls enhanced with neon green markings outside the train station – if public walls were fair game for Zagreb’s hoodlums, why not an underground bathroom? I wait for the hiss of spraying paint. Nothing. He keeps shaking the can. I consider the possibility he is low on paint, but the shaking sound is faint; a desperate law-breaker would shake his can with more gusto.

I realize he isn’t shaking a can. I start to worry. He’s shaking something else. The thought settles over my stall like a phallic storm cloud. I flush my toilet in hope that the heralding sound will frighten him into retreat. He is unperturbed. Whatever he is shaking, he still shakes it even after he must be sure someone is sitting on the pot six feet away from him. I know I have to leave that stall, sometime, someday, sooner rather than later. But still I hesitate. Whatever he’s shaking, I don’t want him to shake it at me.

I take a deep breath, gently press on the stall door. It creaks open. I hold my neck rigid, trying to resist the temptation to look down, resist the temptation to see the shaken. Instead I look at his face. He faces the urinal, focused, relaxed. His eyes are closed. His heavily mustached face gleams with beads of sweat, the sweat induced by concentration. He appears to be somewhere else, mentally transfixed in the place where your fantasies shirk the prudishness of civil society and any sexually degraded act you can imagine plays on repeat. I stand in the stall’s entrance for three seconds, maybe four, paralyzed. Against all volition, I lower my gaze.

I’m up the stairs and outside the bathroom in eight seconds.

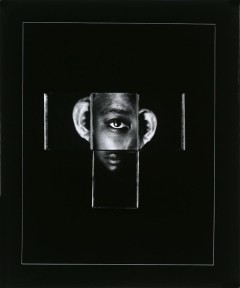

My memories of Zagreb will always begin and end with public masturbation. I remember the post-card quality cathedrals, but the mental images of stone eaves and pointed, terraced towers are forever juxtaposed with genitals-in-hand.  I had expected a snapshot of medieval life, a peeping hole into the past – a living, breathing museum. But seeing that man stroke himself reminded me that no amount of romanticism can mask the concrete reality of a city –it is full of people, and sometimes people need to shirk convention, to take care of primal, visceral concerns.

Kayleigh was confused when she saw me finish sprinting up the stairs. She asked me why I had sprinted, why I was grinning. I asked her if she saw the guy who went down the stairs after me. She said no. She was looking at the park to the left of the underground stairs. She had already lost interest in the source of my sprint and grin. She kept staring at the park, the green made vibrant by sunlight escaping through the loose stitching between rain clouds, barely listening to my story.

One Comment

Leave a Reply

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney

Daniel, what a great article. I was riveted to your journey and thoroughly enjoyed the surprise ending :). Well done!!!!