Music Shaun Scott — July 31, 2014 11:19 — 0 Comments

Jay-Z and Beyonce – Shaun Scott

As the twin towers of American cultural capitalism in the 21st century stood tall in Seattle’s Safeco Field last night, I imagine they felt something like the Seattle Mariners will when they return from their 6-game road trip to that same stadium: “Here we are. What’s next?â€

A 162-game baseball season that spans 3 seasons probably isn’t that different from a summer tour with 20 dates in 35+ days—at some point, rote professionalism overrides performance anxiety, and histrionic proceedings boil down to hitting one’s marks. Fielding a routine groundball to 3rd base that takes a tricky hop really isn’t all that different from nailing the transition from “Love On Top†to “Izzoâ€â€”it’s great, but performances so apparently flawless don’t just wake up like that. They’re tested, conceptualized, debated, and rehearsed so endlessly that the show’s real achievement— far from any one bit of choreography that would give you or I a sure-fire hernia if we tried it—is in its ability to maintain the illusion of spontaneity.

Of course, nothing with this much money on the line isn’t pre-meditated to the last step, right down to remembering where to name-check “Seattle†in lyrics that might’ve originally shouted-out Cleveland or Los Angeles. And at this stage, Beyonce and Jay-Z are corporate entities whose main asset is reminding us of the costs, benefits, and context of their arrival as corporate entities. Last night, in song after song, ownership of the billion-dollar Carter Industrial Complex is asserted, reclaimed, historicized, and then shared—and it’s the Carters themselves performing this commentary. That much self-importance and entitlement is needed for a night of perfect entertainment, but the average relationship simply isn’t drawn to the same scale.

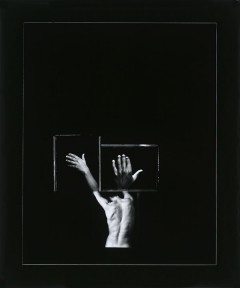

Despite how convincing moments of emotional vulnerability within the world projected by the two can be, the conflation between their hurt and ours is the residue of a distracted society where the memories and struggles of celebrities are encouraged by various cultural vectors to become ours vicariously. There’s a reason why shows like this necessitate extremely bright lights, thumping sound systems, and multiple screens to convey their message: the entertainment value is great, but the spectacle also lubricates the suspension of disbelief needed to accept the show on its terms. Moments of critical reflection would reveal that we have significantly more in common with the boorish people sitting in our section than with the 2 performers who we’d clothesline the boorish people sitting in our section to get a better look at. So the stage set-up wasn’t too dissimilar from your above-average stadium rock display: a bandstand flanked on either side and in the middle by 3 giant monitors.

Now, what Jay and Beyoncè displayed on that stage was nothing short of what you’d expect iconic performers to deliver: a mirror in which cartoonish distortions of ourselves are indulged for a few hours as true. In the 21st century, even (and especially) individuals with nothing much to offer in the way of artistic output are told that they, too, have the opportunity to build and maintain “personal brands†with social networking websites and quick access to digital recording devices. Our personal profile pages give us the ability to align ourselves with any single artifact—a gangster movie, an essay by Frederic Jameson, a Ronald Reagan speech—from the storehouse of human

knowledge that is the internet. Using video filters, transitions, and various Final Cut Pro plug-ins that you can find and download in the space of time it takes you to read this article, the screens behind the power couple displayed a meticulous and meaningful short-film that featured the couple in typical outlaw iconography befitting a tour entitled “On The Run.†As a filmmaker, I was impressed by the inclusion of cinematic illusions to classics like “Pulp Fictionâ€, “Bonnie and Clydeâ€, and above all “Breathless.†The film provided a running visual narrative for the aural proceedings that included several songs—“Public Service Announcementâ€, “Never Changeâ€, “Hard Knock Lifeâ€â€” that were in any case heavily influenced by movies like “Scarfaceâ€, “Goodfellasâ€, and the “The Godfather.â€

The cinephillic gestures will probably go over well when the tour concludes in Paris— that is, if notoriously sharp French cultural critics aren’t so drunk on wine and Marx that they’ll see right through this appropriation of classic cinema, and instead take the tact that George Packer did in his 2013 profile of Jay-Z in his book, “The Unwindingâ€: the line of argument that interprets Shawn Carter as the star of a new millennium minstrel show, where post-industrial capitalism masquerades in blackface to mask just how insidious it is, as if sexism and ribald materiality are suddenly supposed to be “liberating†when mimed by well-manicured female or Black hands.

A brand as big as Jay-Z’s or Beyonce’s is sure to attract detractors who can make compelling cases—but successful brands also succeed in leveraging broad symbols and moods to connect with their customers. Sometimes, on sunny days, I put on khaki shorts and take my blonde girlfriend out for an ice-cold Coke, just to feel like the people in the commercials. As a Seattleite, the Kurt Cobain karaoke stanzas of “Magna Carter/Holy Grail†suddenly had an added weight when recited by 50,000 people in the hometown where the 90s rocker took his own life 20 years ago. As a black man, I was moved to see a montage with grainy black and white images of various Hip-Hop luminaries who’ve been caught-up in America’s criminal justice system. The mugshots of everyone from Rakim to 50 Cent to Tupac to Jay-Z himself reminded me of just how far rap has come— from criminalized child of Reaganomics that matured in neighborhoods under constant police surveilance, to grown-up billion dollar industry with enough cultural clout to sell-out cities like Pasadena and…Winnipeg?

When Jay-Z and Beyonce step out in public, they do nothing if not comment on their own relationship, utilizing it as a piece of performance art. Fans and critics who look for signs of their allegedly deteriorating/allegedly happy relationship completely miss the point: whether the relationship is failing or succeeding, their gifts as artists and individual performers are substantial enough to interpret the ebbs and flows of that relationship musically. It’s a level of personal and professional mastery that outlives empires, even as it finds itself firmly at home in them.

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney