Essays Ahsan Butt — January 21, 2014 11:29 — 0 Comments

Inspiration and Perversity in Cumbaya – Ahsan Butt

It had all the makings of a night that would fall through. The logistics were becoming more complicated by the second. Last minute costume shopping had been a bust. The hour long commute to the party was beginning (*maybe*) an hour late. So while we huddled around the passenger-side window of a cab pleading with the driver to let all 5 of us in — against the literal law, but in the spirit of the compassionate Virgin, who was hanging from his rear-view mirror — the prospect of driving through Quito to costume-lessly attend a Halloween party whose host I didn’t know lost any lingering appeal. It felt like a night that would leave me disappointed, quiet, and utterly uninspired.

I was mistaken.

The cab driver relented and took all five of us up and through to Cumbaya, a rich city north of Quito. We clung to a highway scaling dark hills and surrounded by palm trees, something out of Mulholland Drive. Whenever the trees disappeared, the little fires of Quito lit our view.

We pulled up a quiet street with gated properties to our left and a concrete wall on our right, marking the edge of the hill. Val was on the phone confirming the last few directions when a gate ate its own tail and revealed a way in.

It grew dark as we got further down the path away from the streetlights. Palm trees towered on the right and hung over us. The path seemed to stop in 100 meters, but there was nothing at the end. As if to answer the mystery, a woman in a red 18th century dress came around a corner we couldn’t see. I shot a look over at the others. Val was smiling. This was her friend, Jen.

We followed Jen to the end of the path and then to our right into a clearing. In front of us was the most incredible artist space I’ve ever seen.

There was a handful of people seated at a table with fruits and shish kebobs and drinks. A stoic dog wearing a shirt sat still at the foot of the steps leading up to them. But behind the people and dog — was a two-story living and ART-ing space. I shook some hands, one pair owned by a guy named Carlos, but the dream behind him was still coming into focus, and as it did, so too was the early 90s Dre-infused hip-hop whining and funking from within.

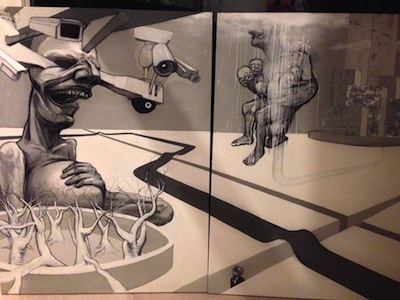

It turns out we were in the back of the home. A glass door was open leading into the kitchen, but really the first floor was all one space. It was sparse with only a few articles of furniture and so there were so few objects to absorb the energy radiating off the walls that the air itself was charged, because on the walls hung these massive paintings and these paintings were the result of psychic fucking where base elements of psyche created offspring that were then tweezed out of the mind, still buzzing and themselves now looking to fuck.

I walked right in and around to one corner where two paintings hung on adjacent walls. It was all so audacious — the images, the space, everything. People were doing social things behind me while one of the paintings flirted with me grossly. Then Val appeared next to me. “Amazing, huh? Jen’s boyfriend Carlos painted everything.â€

Bart and I were looking at a miniature gallery with mini-paintings in it when Carlos came over to us. He was clearly enjoying that we were gawking at his pieces. I told him how much I loved one mini-painting in particular, where these creatures in suits were laughing at another who had tumbled down some stairs. The creatures had no eyes.

He told us he had the large version of the mini-painting back in Poland. He had done an exhibit there and left it. Then he went into a corner and came back with a stack of wooden frames. One by one he sifted through them showing us works he hadn’t yet hung up around the house. He went through them without pretension or seriousness or needing us to see the work a certain way. He went through them — joyfully.

Carlos’ work is completely unself-conscious. He’s comfortable in the domain of the grotesque and finds specific expression there, not specific in the sense of depicting environments and forms realistically, but specific in its expression of relationships, energy, and status. His subjects are deranged by their emotion and it reads instantly. The expressions are at once specific and vivid, but also complex and take unpacking with respect to the surrounding stimuli. Most of his images at once provoke a laugh — they’re perverse and funny. There’s a devilish glee and you want to clap along with the exploits. Then their totality washes over you and you start to see more.

It’s kind of the same with Carlos.

Half-Ecuadorian and half-Polish, Carlos is actually Carlos Kossak. He speaks Spanish, Polish, and English. His English has a lot of character. When he stalls mid-sentence, it’s not because he doesn’t know how to finish what he’s saying, it’s because he’s looking for an amusing way of saying it.

He was born in Poland in 1981, a particularly bleak time including martial law, a crashing economy, and various crackdowns on labour movements. A few months after his birth, his parents moved to Ecuador. But it’s Poland that comes through in his steady stream of anecdotes. At some point (the timeline became fuzzy to me), he moved back to Poland and spent some growing-up years there. He lived on one of the streets where Roman Polanski hid as a child, escaping Nazi persecution after his parents had been sent to concentration camps.

Carlos grew up surrounded by ‘leetle’ criminals who indulged in minor vices. They were his friends. His first muses. He described with endearment the drug-dealers who organized a shift-based around-the-clock watch when thieves began stealing on their street. It was impossible to continue their dealings when the police were constantly around taking reports from the robbed.

The 90s were especially tough in Poland. After the removal of Communism from the system and the genuinely incredible ‘Solidarity’ worker’s movement was hijacked by Western neoliberals promising huge debt relief (my read, not his), the situation was bleak.

He tells of a childhood friend who had a little shop on a train stop. The stop had little value as a market and the train eventually stopped stopping there. When he met his friend again, he was a desperate and unsettling version of the friend he once knew.

Diplomas were shit. No one with a diploma could get a job. Meanwhile, those who spent their time muscling-up came around with big cars, making money as club bouncers or security personnel. If you wanted to study, you had to hide it. It was an embarrassing and ultimately useless thing to do.

In the midst of these depressing prospects, Carlos wanted to be an artist. His parents wanted him to get a profession and he was interested enough, so he studied architecture for two years. But even the architecture was more of an art thing. It helped him with his technique and understanding of space. His father, the Ecuadorian half, was an architect himself. He actually built the dream house we were in, improvising the design as he went. It was meant as a studio, but it turned out so beautiful that Carlos saw it more as a gallery.

I didn’t ask if Carlos’ family was rich. It seemed a rude question. After all, this wasn’t an interview (though I did consider dropping all pretense and asking for one). I really wanted to ask. Every artist I know dreams of a setup like his and I wanted to know how he got it. His family was rich enough to get out of Poland and did buy this beautiful plot of land in Cumbaya, but it’s unclear to me how it all went down.

The studio was on a hidden floor. First we went up the stairs to the second floor, passing a striking black dress hung to the ceiling with a wooden bar and elegantly tied chains. (His parents bought that dress for almost no money at a market in Quito. It turned out to be an Oscar de la Renta original.)

From the second floor, we went outside and took a short set of stairs up and pushed through a door to the hidden studio. It was all one room, littered beautifully with half-paintings and sketches and reference materials and paint.

We flipped through Carlos’ scrapbook and sketchbook. His scrapbook is where he keeps reference images. He likes to cluster them to create amusing relationships or demonstrate a theme. “I love politicians.†He showed us a page of Vladimir Putin images from childhood to his KGB years to the Putin we know now. His expression is the exact same in all the pictures, or as Carlos puts it, “Putin has the same face since he was four…he’s a bastard.â€

Carlos’ sketchbook, on the other hand, serves as the dating service for his subconscious fuckery. The book is actually pristine like the house, mainly because Carlos’ lines are so strong and confident. We went page by page calling out what we noticed or liked.

Jen moved closer to Carlos and kissed him as we fawned over his work. Jen, clearly a woman with her own interesting story — which I didn’t get much of because I was man-crushing on her beau, also lends energy to Carlos’ artistic libido. When we get to a page with a dizzying maze of sexual acts, she tells us how when stuck in a car on a listless rainy day, she read out loud passages of Charles Bukowski’s extremely explicit novel, ‘Women.’ Unbeknownst to her, Carlos wasn’t passively listening — he was listening and also sketching the raunchiest and most impossible orgy he could. Her commitment to reading everything including the sexual onomatopoeia was also inspiring to the driver, who knew no English, but at one point snapped off the radio to listen.

Carlos loves cactuses. In fact, He has 150 cactuses. He showed us his narrow island of soil wedged in the back of his home. Apparently if one cactus is dying and starting to fall over, the one next to it will start to grow faster to hold it up. He showed us a little one leaning against a longer one. “Somehow in the soil, it’s like a cult.â€

There’s another point of interest. If you cut a bit of the green skin off, just a few centimeters, and boil it for 10 hours, you can brew a tea that is a hallucinogen. On his inaugural trip, his paintings started to animate and his towers began to breathe. His friend Jimmy called out one of the cactuses. He said they call it “St. Peter.†It holds the keys to the sky.

Somehow the conversation always came back to Poland. Hooligans and skinheads dominated the scene in the 90s and 2000s. When the European Union finally opened its doors to Poland in 2006, the hooligans immediately went through them. London, Switzerland, and Alicante were among their favourite destinations. When Carlos studied in Spain, anytime he heard Polish on the bus, he made sure to speak Spanish. “It was the worst Polish [from these hooligans]…like you were so in jail!â€

The hardships of Poland engendered a nihilistic culture, one Carlos says he doesn’t enjoy. He prefers the Ecuadorian way. But this I don’t buy. His artistic currents stream from Poland. You can see it when he simultaneously criticizes and relishes Poland’s black humour.

In 2010, ‘twin right-wing psychos’, the Kaczyński brothers, won office. The people were stunned. “’How did they win?’ You didn’t vote. The city didn’t vote. That’s how they won.’†It also didn’t help that an entire generation of Polish politicians, including the then-President, Lech Kaczyński and his family, was wiped out in a shady plane crash enroute to Russia.

After Lech’s death, the brothers decided to commemorate the late president by burying him and his wife in a sarcophagus placed in the antechamber to the crypt of one of Poland’s greatest heroes, Jozek Pilsudski. This garnered a collective eye-roll from the people. Lech simply wasn’t that big of a figure in Polish history. A Polish beer company with a beer coincidentally named “Lechâ€, decided to purchase a billboard that was visible from outside the cathedral. When mourners climbed the steps out of the crypt and out onto the streets, they saw the billboard and the beer company’s paid-for message: “Enjoy a cold Lech!†It was the perfect Polish joke. Subversive with enough plausible deniability. Sales of Lech soared.

The story reminded me of Carlos’ dog who sat near-by. His shirt had a message too: ‘Art is survival.’ It’s another subversive message with plausible deniability. If I’m reading the sarcasm correctly, it’s a remarkable statement. Here is a man living out an artist’s dream, in the most idyllic of spaces creating and teaching art for a living, and in three words, he seems to be pointing to the ludicrousness of suggesting art is important. It’s certainly ludicrous to suggest that art is important to a dog. With numerous paintings of his depicting humans as animals, barely more evolved than a monkey, it’s not a stretch to suggest he’s contemplating whether he’s built his life around something that is essentially masturbatory. Does he really believe that? I could see him argue either way and he’d do so with a big grin.

That’s the thing. Carlos is an instigator. He pushes and prods ideas into damning places, but he never loses the laugh. He indicts even himself. He does so with everything in his arsenal. And that’s the other thing that makes Carlos what he is. Whether using his architectural background to create spaces that cannot physically exist or injecting his subconscious with the Zygmut Bauman’s idea of the liquid modernity, Carlos is drawing on more than just painting skill and technique.

It was the same with British comic book writers who swept the American scene in the late 70s and 80s. Guys like Grant Morrison, Alan Moore, and Neil Gaiman. The quality and depth of their writing was far beyond the pedantic two-dimensional picture-books that American writers were putting out at the time. The reason? American comic book writers grew up reading comic books while the British writers grew up on Shakespeare and Aleister Crowley.

And here’s the last thing about Carlos. He told one other story about Poland. When Pope John Paul II was in critical condition, the televisions in the bars followed the news 24/7. When he died and the story broke, the bars shut down immediately. All shops shut down immediately. Without any coordination, the people in the city flocked to a window where the Pope would greet the people on his visits. Within minutes the square was packed with mourners. Carlos described the behaviour as weird, which I think he meant to indicate cultish behaviour. But again his tone belied something else. He’s an observer and I have no doubt he wouldn’t be an artist if not for the fact that he is inspired by the magic he sees — whether it’s drug dealers doing shifts to protect the streets or a spontaneous pilgrimage for a dead icon.

Before the night ended, I asked to take a picture of Jen and Carlos and they graciously obliged. We waited for a cab outside the gate to take us home. There were five of us again. This time I didn’t really care what the cab driver decided. I wasn’t going to tell a person what to be inspired by — the literal law or the spirit of the Virgin was fine by me.

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney