Fiction Sheila MacAvoy — January 3, 2012 13:29 — 3 Comments

Inn Of The Flying Plates – Sheila MacAvoy

She sat in the front seat of the Volvo and opened the L.A. Times as he inched down the driveway and avoided the branches of the pittosporum that needed pruning. She looked up once to admire the sleek lawn and the planting of daffodils that made their house look like an English cottage. Then she heard his intake of breath, as if he were about to comment on those offending shrubs, but thought better of it because they were officially not speaking.

It had started last week. An argument over the replacement of the broken television in the family room. That produced a dialogue of the usual accusations.

“All you think about is your damn job,†he said.

“All you think about is your next drink.â€

They had this argument, or versions of this argument, weekly, even daily, but still they stayed together, squabbling grackles, mated for life. In the beginning they reasoned it was for the children, then it was because of health insurance. Now the children were gone and both were working and insured, and still they never seriously spoke of separation or divorce. Once, when they were both drunk on a few good bottles of Sancerre, he experimented with the dog as their excuse.

“Who would have Buster?†he said.

“I would, of course. I brought him home on a whim and convinced you to keep him. He wasn’t your idea.â€

“Who fed him, walked him, took him to the vet? No. Buster belongs with me.â€

“How can you say that? Buster sits at my feet every night when I’m reading.â€

“I have to admit, you two look cute that way.â€

“Nice. A wife and her dog. Both cute.â€

“You’re tipping your glass. It’s dripping on the rug.â€

Then Buster fell in love with a motorcycle and got badly mangled. They had to be put him to sleep, so there wasn’t even that last excuse. There was a sentimental inertia to their long attachment. Once the ultimate remedy was uttered, they knew there would be no retreat.

* * *

After the short drive from their house in the canyons of west Los Angeles, he took the looping connector that spun onto the I-10 freeway and moved over to the diamond lane, changing lanes with breathtaking efficiency. Sometimes she closed her eyes when he was demonstrating his skill at freeway driving. In the diamond lane the traffic was pretty level at seventy miles an hour so they would reach Rancho Mirage and their condo in less than two hours. Not bad for a Friday in spring. After driving in silence for forty minutes, she finally spoke.

“Did you bring SCRABBLE?â€

“I did.â€

At the junction with Route 111, he left the freeway. The road went directly through the main street of Palm Springs with its T-shirt shops and glut of fake turquoise jewelry stores. She resisted comment about what seemed an unnecessary detour, but after five minutes she wondered why they were parked in front of Vons supermarket, afternoon traffic streaming by.

“Did we have to subject ourselves to this?†she said.

“I thought you might need some groceries.â€

“There are grocery stores in Rancho Mirage.â€

“Yes, but they’re such gougers.â€

“I don’t want to go in.â€

He turned off the ignition, opened the door, and got out. She watched him walk away toward the supermarket, patting his back pocket to check for his wallet. He was as slim as when they first knew each other, his light-brown hair a little thinner, but only barely touched with white. He kept it short at the temples to conceal the grizzled look, and his loping stride reminded her of their earlier, lovely days. After several minutes in the sweltering car, she turned on the ignition for the air-conditioning.

When he returned he was carrying a plastic sack, obviously a couple of bottles of wine or liquor, and some other small item. Probably peanuts. He opened the rear door and dropped the parcel on the backseat next to his tennis racket.

“All the basic food groups,†he said, putting the car in gear and sprinting off to the next traffic light.

“We’ll still have to stop for food,†she said.

“That’s your problem now.â€

“Thanks, asshole.â€

* * *

When they got to the apartment, she turned on the AC and opened the blinds. In the patio, a dead geranium lay slumped in its clay pot and their outdoor chairs were covered with a layer of fine-grained dust from the most recent fire in the San Bernardino Mountains. He opened the fridge and pulled out a tray of ice cubes, banging them into the ice bucket on the marble-topped bar.

“I’m going for a swim.†She stepped out of her cargo pants and walked toward their bedroom.

“What’s for dinner?â€

“Beats me.â€

“I thought maybe we could get something from that new gourmet takeout on Rivoli.â€

“I don’t feel like it,†she said loudly from their room.

“Where shall we go?â€

She came out of the bedroom in a one-piece swimsuit made of pale peach-colored latex. For a second, she looked naked, still slender and curved with good legs.

“Whoa,†he said, and sipped his Scotch.

“How about The Casablanca Inn?â€

“We’ll always have Paris,†he said.

* * *

The headwaiter led her to a table in the corner, away from the fountain. She glanced at her husband, who had followed a few steps behind. He saw the restrained contempt on her pretty round face surrounded by its cloud of golden hair.

“I asked for a quiet table,†she said.

“This looks quiet over here in the corner,†he said.

She raised her hand to her pearl necklace.

“It’s next to the busboys’ station.â€

“Do we have anywhere else?†he asked the waiter.

“Only near the fountain. You have to make a reservation to be anywhere else.â€

They took a table near the fountain, she with her back toward the incessant tinkling.

“We are now nowhere else,†he said as the waiter pulled out her chair.

Overhead, a skylight sent beams of evening sunshine into the room and over the dark red Saltillo tiles which surrounded the fountain. Beyond that Moroccan touch, a pale carpet covered the rest of the restaurant.

She lifted the bundle of tableware rolled up in a napkin and spilled out the implements, smoothing the cloth onto her lap. He removed a pack of cigarettes from his inside jacket pocket and lit up.

“You can’t smoke indoors anymore,†she said.

“Let ’em stop me.â€

“You’re embarrassing me. How much did you have to drink before we left?â€

“Don’t remember.â€

“Oh boy,†she said and picked up her menu.

* * *

They were still waiting for their salads when a waitress from across the restaurant passed the splashy fountain, busing a pair of plates with the remains of a shrimp diablo dinner. One green pea and a smidgen of chopped lettuce, soaked in the remains of a too-oily vinaigrette, slipped off the edge of the top plate and onto the tile flooring.

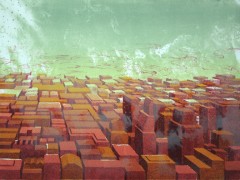

Such a small thing, a bit of food on the floor. By this time, it was 8:15 p.m., the dinner service at its crescendo. The next waiter, who exited from the kitchen with a full load of dinners on a tray, took a shortcut past the fountain. Before the waiter reached his destination, his right foot came in contact with the green pea and the smidgin of lettuce lying in wait on the polished floor. His left side was dedicated to holding up the tray on his shoulder, both hands gripping the rim of the tray to steady the heavy weight of spaghetti in clam sauce, chicken l’orange, steak Moroccan. The waiter lost his footing when the sole of his shoe contacted the green pea and the oily lettuce. His feet flipped forward and his rear end smashed into the tile. In a pyrotechnic display of the laws of physics, the thrust of his arms and shoulders attempting to control the service tray propelled the load into a spectacular upward spin which distributed the full plates and sauceboats in a spiral of matter similar to the Andromeda Galaxy.

* * *

“So, I guess I better tell you,†he said.

“What?â€

“I got fired.â€

“You what?â€

“I got fired. Yesterday.â€

She put down her fork and took a sip of water.

“They gave me two weeks notice and wrote out a check and told me to clear out my desk.â€

“Did they say why?â€

“They said I cheated on my expense account. Which I did. But so does everybody.â€

At that moment, the waiter passed on his way to the table in the far corner by the busing station, the table they had first refused. As he made his misstep, and the filled plates of food were sent flying up towards the skylight, the waiter sprawled onto the tiled floor. Plates, aluminum sauceboats, and food were so forcefully flung that every baby carrot, julienned string bean, strand of linguine, and half chicken could be identified. As it all came down, plates shattering on the floor and plopping into the pool, the food spread indiscriminately over the nearby diners. Most of it hit the waiter. At first there was a shocked silence, then exclamations of disbelief. Finally, each table assessed the damage.

“You have a slice of orange on your shoulder,†she said.

“You have spaghetti on your head.â€

She reached up to her recently frosted hair and felt around for the pasta, her face white and lips trembling as she suppressed what looked to him like her gathering panic. It surprised him, her panic.

“They fired you?â€

He reached across and extracted the bit of food from over her left ear. There was a tenderness in his movement and a softness in his dark eyes that she had not seen in months—maybe even years. He lifted the orange slice from his shoulder and placed it in the bread tray, along with his spent cigarette and the strand of pasta.

“That’s linguine,†she said.

He leaned toward her as a man at the next table began wiping a green coulisse from his female companion’s back.

“Was that some kind of cosmic message?†he said.

Around them a team of busboys and waiters worked furiously to clear away the wreckage and to pacify the customers before their shock turned to rage. The waitstaff’s intensity caused more chaos as they slipped and slid over the tile floor. The manager emerged from his office and went from table to table assuring everyone near the fountain that their dinners would be on the house. The manager’s shoes soon became spotted with food and sauce of differing colors. One table of four stood up and left, gingerly stepping over the mess on the floor. A teenager dining with an elderly couple, most likely his grandparents, stood at his place and snapped a photo with his iPhone.

“Awesome,†the kid said.

* * *

As they waited for the car to be brought up, she slipped her arm through his and leaned against his side. He patted her hand.

“Where will you go?†she said.

“I don’t have a clue.â€

“There’s bound to be something. You have loads of experience.â€

“That might be the problem.â€

The car came up and he waited to open the door for her, a gesture which he had not bothered with for a long time. She noticed that he tipped the carhop with a fiver.

He pulled out of the lot and headed into the spring night. It had been an unusually hot day and the air was clear and smelled of night-blooming jasmine, as if the atmosphere had been seared clean by the sun. They didn’t talk, but soon he could tell from her shallow breaths that she was weeping.

“I’ll find a place. Don’t worry, babe. It won’t be as good, but I can always do income tax filings. Much as I hate it.â€

At that, her composure collapsed and she was overcome with heavy sobs. He was doing income tax filings when they first met thirty-eight years ago. She sobbed loudly until they got to the complex and he was angling the Volvo into their space. She got out of the car and, as they walked across the pavement, she stopped and looked up at the pale beige building with its Mexican tile roof. Bowls of fuchsia hung from the corners of the small balcony outside their bedroom.

“I guess we’ll have to sell the condo,†she said.

He laughed, a little bark.

“To whom?â€

3 Comments

Leave a Reply

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney

I love Sheila MacAvoy’s writing. this is the second or third story of hers that I have read and it fills me with such sorrow and longing. I sense the feelings between the two people and feel the hope that just might happen. It is a beautiful story. Thanks.

Another pitch-perfect story … or the usual for Sheila MacAvoy-

Wonderful imagery, hilarious sarcasm amidst the mundane reality of middle age. A very real quality and a very entertaining, insightful piece.