Essays Shaun Scott — December 4, 2014 13:41 — 0 Comments

Enemies Like You – Shaun Scott

With ratings revenue securely in hand from last week’s pilot episode, CNN’s as yet untitled smash hit television series revolving around dead black bodies in the street was renewed for another week. On Wednesday night’s installment, the setting was moved from rural Ferguson to New York City, where main character Eric Garner was left breathless on the hard, hot sidewalk by a gaggle of police officers back in July of 2014.Â

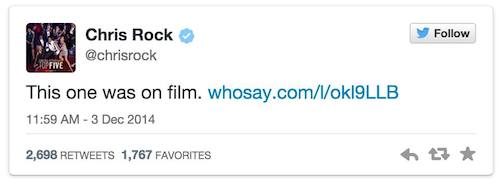

With so many storylines surrounding police brutality saturating social networking and cable television, it was inevitable that Garner’s story would fall between the cracks (in the pavement where police callously left him to die). But the resurgent narrative surrounding his death seems to’ve hit a national nerve where even Mike Brown’s couldn’t. As Chris Rock put it…

A black body in pain has been one of America’s greatest muses since the first unhappy African arrived on its shores in 1619. You bred slaves to entertain you when you were bored on the plantation. You’ve sung minstrels since at least the 1840s. You ate barbeque under black bodies swinging from poplar trees throughout the 20th century. By the same token, archival images of blacks being flushed down sewer drains in the 60s still animate your greatest social justice movements, gay rights and immigration reform included. And what—other than dance moves of Beyoncé that would make you sore for weeks if you tried them—is more consistently inspiring to Americans than watching black men gracefully exert themselves between the lines of play of professional sport?

Truth be told, America is fascinated with black bodies: it finds our proportions and movements enviable and comedic. Our speech occupies the middle ground between poetic and earthy. Our discomfort is entertaining. Our pain is yours. You’ve been staring at it since you saw us. Black pain on camera has been trending all year. “I hear you saying she was knocked out in the elevator…but is there video?â€Â

So kudos to CNN for refocusing a national attention span temporarily led astray by Kim Kardashian’s bare soapy arse. We’ll talk about Wednesday night’s episode in a second—but first, some self-disclosure: the last week has been fucking depressing. Social networking’s distorted reality amplified the silence of friends and colleagues on the issue, and led me to flirt with the dangerous idea that politics are purely entertainment that one has the option of responding to or not. Is this a line-in-the-sand moment, or do these people and I simply watch different television shows? Dancing With The Stars for you, The Racial Apocalypse for me.

Then came the news of Eric Garner. This one was on film. Those cops didn’t just kill Eric Garner—they killed any tolerance I had for the moderate position on 21st century life in America. I’m done. No more sitting on the fence. No more masks. I need to see who is who. I may be projecting here, but let’s get a couple of things out on the table:

1) There’s a fair chance you didn’t remember or even know that Eric Garner died until you saw his story revived on social networking with the news that the officer who killed him was acquitted by a Grand Jury. I’m in that boat, and I don’t think there’s any shame in it. National news cycles have saturation points, and this is why social networking is so important. Our real friends fill us in on things that matter when we were too busy making a play on Tinder to know the cops choked a dude out on camera.

2) The last time you gave any serious thought to Staten Island, where he died, probably involved the Wu-Tang Clan. No shame in that either: no lie, the night of the Michael Brown verdict, after turning off the television, I wanted to hear 2 songs in specific. One was John Coltrane’s rendition of “What’s New?â€, mostly because of it’s profound melancholy and suddenly poignant title. The other was Wu-Tang’s “Bring Da Ruckus.†When I read that New York Times about Garner’s death that everybody shared around in the afternoon, I got a sick sense of amusement to realize that Garner and Wu Tang hailed from the same place.

When I made it home, I turned on the television. Anderson Cooper asked a panelist “If the NYPD would escort these protestors all night, or let the situation breathe,†then apologized for his poor choice of words. Filmmaker Spike Lee made an appearance, and described getting on his bike to catch up with protestors the night of the Michael Brown verdict. That was all I needed to hear to leave my pad, board a bus, and look for a fight.

It didn’t take long: a congregation of 75-150 protestors was occupying a busy intersection here in downtown Seattle. At first I chanted, but eventually I just wanted to hear “Bring Da Ruckus†again. My massive headphones doubled as earmuffs in the 30° weather. I walked the streets that night, arms raised in the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot†pose popularized this week by the St. Louis Rams, lowering them only to recue this Wu-Tang track that’s invaded my life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbfGkiecl2M

As it turns out, 4 minutes and 12 seconds is exactly how long I could hold my hands above my head in proto-freezing weather before they needed a break. At some point, as the march neared The Space Needle, RZA’s use of samples from horror flicks and Kung Fu films was brought into perspective: they’re the sounds of survivalism, the songs of a community under siege, the soundtrack of the borough where Eric Garner lived, was arrested 30 times, raised a family, and was choked to death. Somewhere, somebody who was indifferent to the life of Eric Garner and hostile to the motives of protestors like us was bobbing their head to Wu-Tang. If not today, then tomorrow. It may as well be going in one ear and out the other.

Because for most Americans, The Black Experience is like a raging party that nobody wants to stay at past a certain hour. The food is exceptional, the art on the wall is mind-blowing, and of course the music kills it. But eventually there’s a helluva mess to clean, and the cops always show up. It’s our house, so we can’t exactly leave. We know who stayed and who left without helping: we don’t always call you out—but we know. And we don’t show it—but we’re a little less happy to see you next time you come over. We tried upping the price of admission, but it’s never expensive enough to keep you away. We keep saying we’ll stop sending you the invite…but we always seem to:

Because with enemies like you, who needs friends?

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney