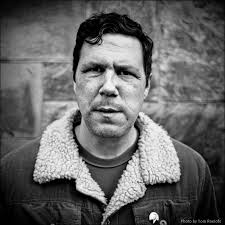

Editorials Jake Uitti — February 17, 2014 11:27 — 0 Comments

The Monarch Drinks With Damien Jurado

Before sitting with him, I had no idea the influence songwriter Damien Jurado believes God has on his life.

Marco Collins, Damien and I meet in the hallway of The Original Pancake House on the corner of West 15th and 80th on a Saturday morning. After exchanging gossip about which Seattle singer is doing well in Paris, the largest show Damien ever played and who The Posie’s Ken Stringfellow is working with over seas, the three of us take a seat at a table in the middle of the quaint, hard-wood restaurant. Our waitress brings coffee, as other servers distribute plates of waffles, omelets and giant breakfasts. A few minutes later, she takes our order for pancakes, eggs, hash browns and bacon (the best in town, according to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame DJ, Marco).

As we sit sipping our drinks, Nirvana’s In Utero comes up. Damien talks about the distinction between the album and its predecessor, Nevermind. “The screaming— there’s a big difference between what you hear on Nevermind versus the deep, burning gut screaming on In Utero—it sounds like Kurt’s vocals are bleeding. There’s that line where he just says, ‘Go Away!’ but he’s screaming so hard it distorts the microphone. It’s like he’s shouting to everyone that’s around him.”

I didn’t know it initially, but as our conversation unfolds, this comment proves supremely important. The popular sheen that a type of production can do to an otherwise organic music—distorting not a sound but an ethic. It’s why Damien, who recently put out his thirteenth full-length album, Brothers and Sisters of the Eternal Sun, says Nevermind felt like a betrayal to him and the entire genre of Punk Rock.

Marco, sipping coffee, tells the story of Kurt’s intervention, which occurred a week before he committed suicide. A friend of his, he says, was present for the event. “Kurt was staring out the window, measuring to see if he could scale the building and escape.”

“When he killed himself, were you shocked?” Damien asks. “Because I wasn’t shocked. I think it was how he died that shocked me. I just thought it was going to be an overdose. He didn’t strike me as a violent person—I didn’t realize he owned guns.”

A waitress comes around and refills our coffees. I add cream, sugar. Damien begins to tell a story, a personal one, about being on the brink. “Believe it or not, I had a spiritual experience. From ages 13 to 17, I’d battled addiction. I’m an alcoholic. I’ve been clean for a while, though I had a relapse in 2006.” The comment does not fall on deaf ears. Marco has publicly battled substance abuse and I come from a family of addicts—both my father and half-brother died from drug addictions. “I ended up becoming a Christian at 17 years old. But from 17 to my mid-30’s I kind of just wavered. But around 2009, I went off the deep end. I didn’t go to church. And in the fall of 2012 I just snapped.”

“What was that like?” I ask, hoping not to go too far.

“In 2010, when I made Saint Bartlett, I was searching,” says Damien. “But at the same time I felt God was—not pushing me away—but hiding himself from me. And I became angry at that. But now I realize it was for a reason.”

Damien describes going on tour with a woman he’d known for many years, a woman who is now his girlfriend. The two found themselves at a beach in Jacksonville, Florida in October, 2012. “I remember looking out to the Atlantic Ocean and I just felt the presence of the Lord hit me. After that, I was never the same. It felt like a physical hand on my back.” The waitress brings our breakfast. Yellow eggs, maple-colored bacon, about a dozen pancakes are set in front of us. We begin to eat. “It was an audible thing,” he says. “A voice saying, ‘Fall back, I have you.'”

Damien had a dream. It was this dream that lead to the creation of his most recent two records. He says that, before this dream, he’d been encasing himself in labels and genres and it was time finally to break out. He uses the metaphor of a child. “You’d want it to be the best it could be, right?” he asks Marco who takes a bite of pancakes. “That’s how I felt it was for me, with God saying, ‘I gave you this talent, don’t sound like everybody else!'”

So how does all this tie into In Utero? Marco wonders. “Nirvana needed to get away from everything and make the album they needed to make,” Damien says. “And that’s how it was for me. Picture a car—I got inside this car, took all the breaks out, and decided to push it down Queen Anne hill.”

What about fear? Marco says the word first: “Fear rules my life,” he admits. “I don’t know how to shake it. I know what it’s engrained in—fear of being gay and growing up that way. I feel like I know how to channel passion, though. But it’s hard for me to take that car to the top of the hill.”

“I know that God has me in the palm of his hands and no matter what I do, I know he’ll back me,” says Damien. But he doesn’t seem like he’s trying to convince anyone of this. He just says it. “Fall back.”

Brothers and Sisters is by far Damien’s most successful album to date, already in its second pressing and charting high in the United Kingdom, despite the fact that Damien and his producer Richard Swift thought it wouldn’t be well-received by the public. “It’s all over the place,” Damien admits. “It’s like a Jackson Pollock painting.”

Our waitress comes around again. We decide to order more pancakes: Marco, blueberry; Damien, buttermilk. I order more hash browns. We can’t help ourselves. Coffees and waters are refilled. It’s well lit in the restaurant, chatter everywhere.

When the second round of food arrives, Damien brings up the idea of children breaking away from parents’ upbringing, from lifestyles that were not their choice. “Breaking from people who say interracial dating is bad, that you shouldn’t be friends with drug addicts. It’s not Christ-like. You have to come to a point where you say, ‘I choose this, but I choose it my own way.'”

Both Marco and I grew up in the church. I was Confirmed, took Communion. Marco went to religious education classes. But he eventually became sick of it. “Punk Rock became the ultimate rebellion for me,” he says. “I would stay up all night recording eight-tracks off the radio and we’d have those for the entire week! Dead Kennedys, X, The Germs, Agent Orange! Once I started exploring the things that scared me, I found freedom.”

“Exactly!” exclaims Damien. “That’s what I’m saying! At the top of the hill, there’s a certain freedom of pulling the breaks out and pushing the car down, knowing someone has you.”

Marco admits, “When I found Punk Rock, these three-chord songs, they challenged everything. God bless Flipper, God bless Siouxsie and The Banshees, because those bands made me open the windows and say, ‘I don’t know what’s coming, but it’s coming.’ In a way, I guess I did have faith.”

Marco Collins, legendary former DJ at The End, credited for breaking dozens of influential bands, grew up in a small mountain town in Northern California. He was a late-bloomer, bullied, looked more pretty than tough in a town of tractor pulls and football fanatics. “I remember the day I told myself I wouldn’t be who I was anymore, even though I loved that person. I remember putting that person on the back burner, saying I couldn’t be him.” Damien puts his hand on Marco’s shoulder. “Trust me,” says Marco, a bit emotional now, “it hurts 10-times more to be called a fag when you are a fag. I had to learn to talk differently, act differently—to be different.”

“Do you feel that person is still on the back burner?” I ask.

“Oh, fuck yeah, man,” Marco says. “Which is why I’m so loud about it now—I’m embarrassed I didn’t come out in the 90’s. Kids write me today saying, “Had I known you were gay then, it really would have helped me.’ Although, I wasn’t the best role-model then.” We take this chance to laugh.

“It took great faith to face all that fear,” says Damien. I look up a moment, plates are being taken to the back. Cups and glasses are refilled. I finish my hash browns. The waitress brings a check and lays it on the table. I realize we’ve hardly scraped the surface on Damien’s new record.

Religion is integral in the narrative of the concept albums, Brothers and Sisters and Maraqopa. Both albums were based on that cinematic dream Damien had shortly after he found God on that beach. The dream begins with a man awakening on his back and with the realization that his life up unto this point has been meaningless. He’s a famous musician but decides now that he’s done. He takes what little cash he has, leaves his I.D., and goes off in his car. Maraqopa is where he goes, seeking anonymity. The man hides out there, but meanwhile his absence is all over the headlines. He leaves Maraqopa later, but gets into a head-on collision with a car (this is where the first album ends). Brothers and Sisters starts with the man thrown from the car, unscathed. He walks back to Maraqopa, but everything’s different. He realizes he can communicate with his mind, telepathically. He finds out he’s a beacon: the one who can tell when and where Jesus is going to return. When Jesus returns, he wonders, will he be taken too?

“It comes down to one thing: what does he believe in?” Damien says. “That’s where my dream ended.”

“Were you pissed you woke up?” I ask.

“No, I got out of it what I needed.”

“What was the compulsion to turn it into a record?” I wonder.

“I was ready to just leave it at the first record,” he says. “I had another record ready to go. And a week before going down, a friend asked me if I was excited to get into the studio again. But, I really wasn’t. I wasn’t that into those songs. My friend said, ‘You can always finish the Maraqopa story.'”

“You wrote that entire record in a week?” exclaims Marco.

“I wrote it in two days,” says Damien.

“It reminds me of listening to AM radio on the school bus,” Marco says.

“You know where it comes from?” smiles Damien. “I’m giving you the secret ingredient to this record, the reason it sounds the way it does. In 1999 my ex-wife got really into vintage Volvos. We owned four of them at one time—they were cheap. And the car that I drove only had an AM radio. I discovered AM 880 KIXI. All oldies, all the time. You know what ties all the songs together on that station? Reverb—you can live in it.”

“Yes!” exclaims Marco.

“And here’s where it comes full circle,” Damien says. “The year Nevermind came out, I abandoned Punk Rock. 1991 was the year Punk Rock broke—not became big, but broke. I was furious, I hated Nirvana at that point. Punk Rock, at some point, betrayed itself. So, I left.”

Everyone takes a sip of coffee. I look around at the people in the restaurant, young and old, people of various body sizes and dress, of various breakfast choices, all eating at The Pancake House, the place where Damien had chosen for today.

“I was interviewed the other day by someone and he asked me,” Damien continues, “Who, in your opinion is the greatest American rock band of all time?” I said, “The greatest American rock band hasn’t been heard yet, and I hope they never are.” You know why? Because that would be the end.”

In an instant I think of the world finding perfection. This impossible thing. This perfect album to put an end to all albums. To put an end to all songs. No one actually wants this—for, as Damien says, that would be the end. The end of everything. The end of a place to live, creatively. And the end of Maraqopa.

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney